I currently work with Professor Zuzanna Siwy in the Department of Physics at the University of California, Irvine. In my PhD research I’ve primarily worked on nanopores and recently began a project in the area of Bio-MEMS. I’ve fabricated systems spanning 4 orders of magnitude in size, or roughly the difference between a meter and a marathon! Besides my experimental physics work, my interests are in computing and data science. Along these lines I’ve written software to perform various tasks, including remote instrument control, automated data analysis, and data visualization. My preferred languages are C++ and Python, and I also love building software in the Qt Framework. Feel free to check out my coding projects on my github page.

Here’s a little bit about my research.

Nanopore?

Nanopores are small holes, typically around one billionth of a meter in diameter. Nanopores are abundant in the natural world, where they help regulate transport of ions and biomolecules into and out of cells. Furthermore, advances in nanofabrication in the past couple of decades have enabled the fabrication of synthetic nanopores as well. Nanopores (both synthetic and biological) are used in a surprisingly large variety of applications, including water desalination, DNA sequencing, enhanced drug delivery, and ionic circuitry. One of the more tantalizing aspects of nanopore research is the ability to precisely control ion and water transport at the nanoscale, which would lead to the possibility of creating artificial cells in the future.

Ionic circuits

Like electrons in the electronics we’re all familiar with, ions can also carry an electrical current under an applied voltage. We can think about recreating novel electronic circuit elements in ionic systems. For example, the ionic equivalent of a diode would permit ions to flow through it in one direction, but not the other. How do we engineer such a system? In short, the answer is to shrink our system-size down to the nanoscale where interesting behavior begins to emerge in the ion solution. As we shrink down, the surface area-to-volume ratio of the system increases, and eventually the charges on the molecules of the channel walls begin to dominate the system behavior. Through clever engineering at the nanoscale, we can create ionic devices with novel ion transport properties.

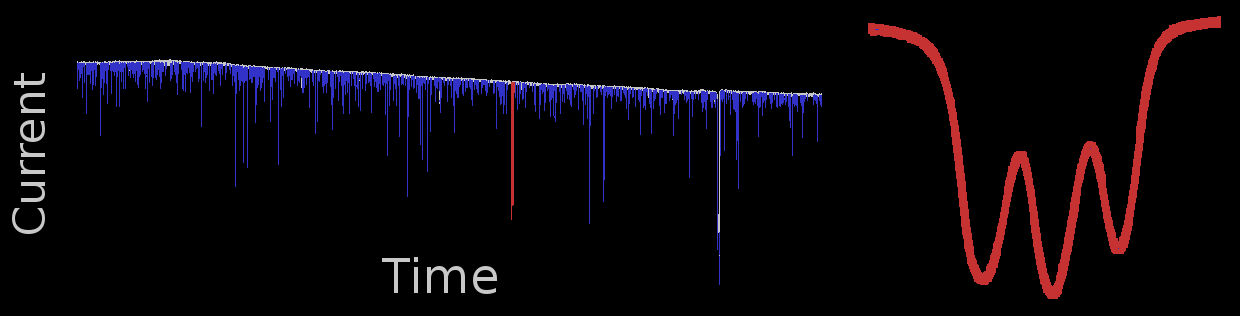

Along with collaborators, I showed that it is possible to create an ionic diode out of a pore with a thin metallic layer embedded on it. To do this, we deposited a ~10 nm-thick layer of gold onto a substrate and drilled ~10 nm in diameter holes through it with a transmission electron microscope. When a voltage is applied across the nanopore, the conducting gold layer polarizes leading to different ion charge concentrations inside the pore at opposite voltage polarities, resulting in an ionic diode.

Resistive pulse sensing

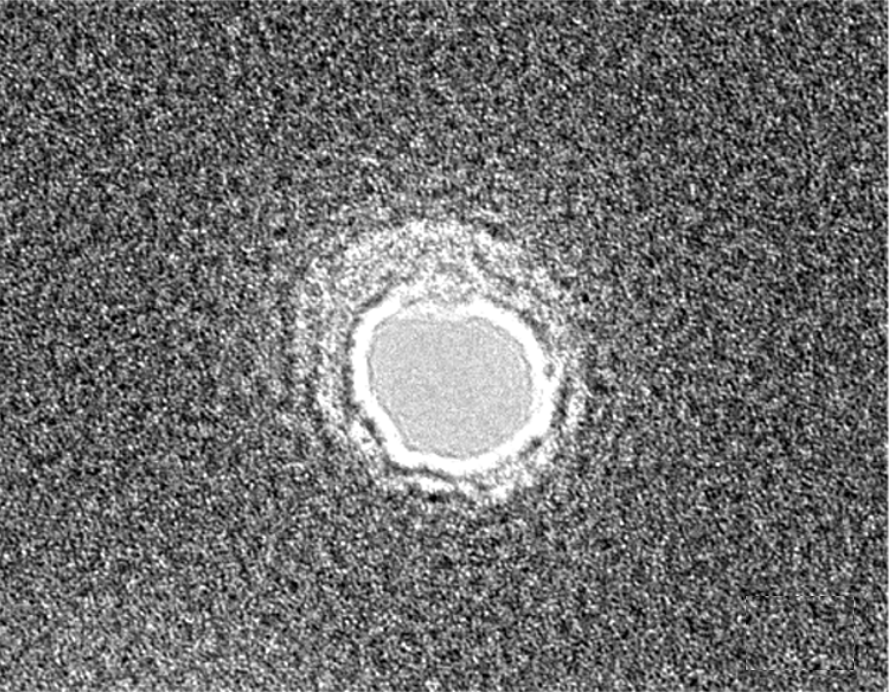

Resistive pulse sensing is a means of measuring the properties of small particles by the conductance changes they induce when they pass through a small nano or microchannel. This technique gives insight into the properties of particles at the nanoscale, where they are invisible to optical detection and are otherwise difficult to study. This technique was originally introduced in the Coulter counter, where it is used to perform red blood cell counts in hospitals. The same technique is also currently being used for nanopore-based DNA sequencing.

I’ve worked towards creating a better understanding of how the electrical signals measured in a resistive pulse experiment correspond to the properties of the particle being studied. For example, I helped show that aspherical objects create much larger resistive pulse signals than their size suggests they should.

Transport in single walled carbon nanotubes

A carbon nanotube is a one-atom thick tube of carbon atoms arranged in a hexoganol lattice. By embedding a single carbon nanotube in an insulating layer we can use the carbon nanotube as a nanopore. These carbon nanotubes can be as small as 1 nm in diameter! Although they are conceptually very simple, they have been shown to exhibit exotic transport properties like ionic conductances and fluid flow velocities orders of magnitude larger than expected. Along with collaborators, I ran experiments on a new platform consisting of a single, 1 nm in diameter, 12 micrometer long carbon nanotube connecting two fluid reservoirs.

Developing a high-throughput cancer cell detector

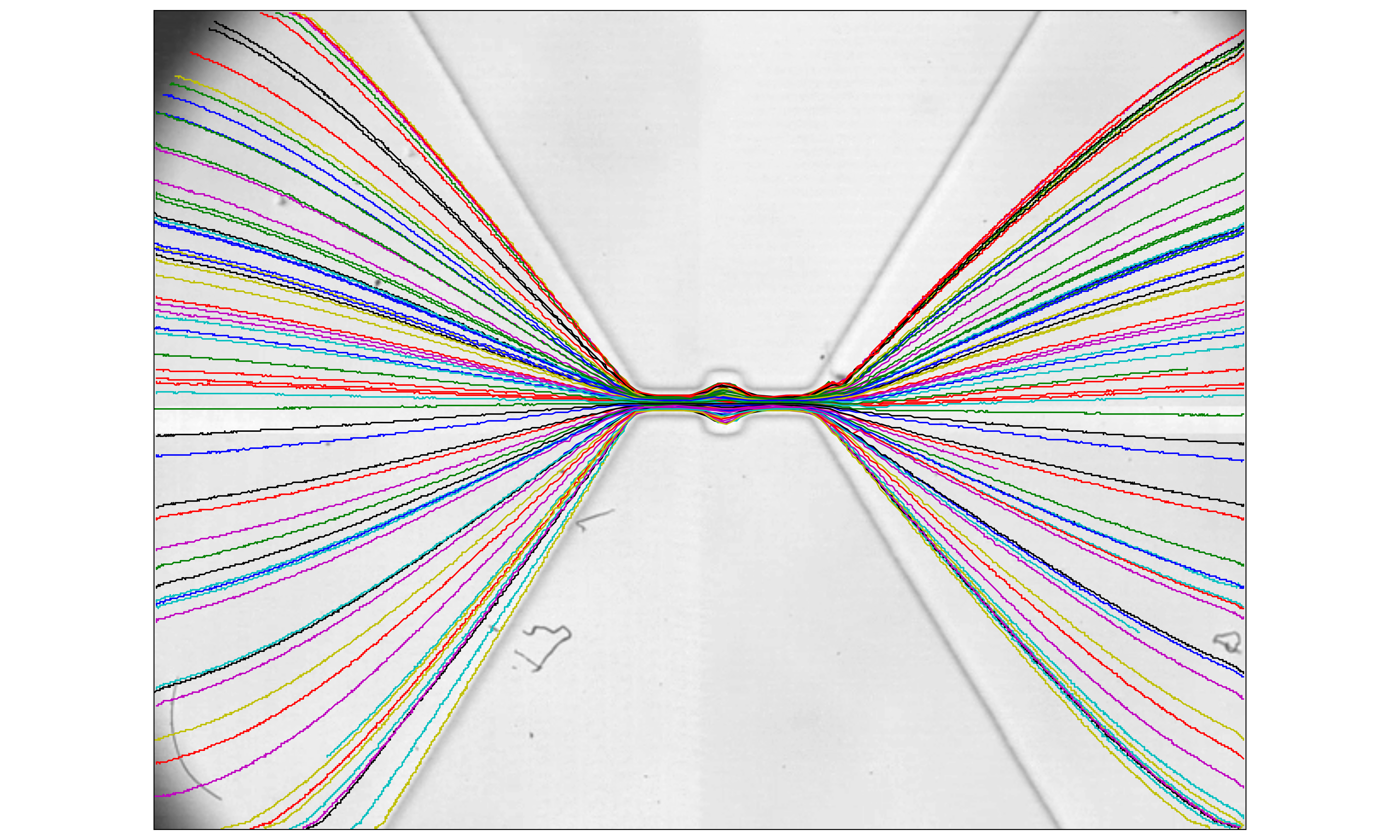

Not all cells are alike, and as it turns out, one key feature that can be used to distinguish different types of cells is how squishy they are. If we could develop a system that can quickly and accurately measure cells’ physical properties, then we might be able to detect cancer cells before the tumor has too much time to develop.

In my research, I build custom microfluidic channels and push cells through them at blazingly fast speeds. The shape of these microchannels induces pressure differences that cause the cells to deform, which I then image with a high-speed camera at speeds up to 100,000 fps! The end game of this research is to develop a high-throughput sensing platform that can measure a cell’s diameter and stiffness in real time, and filter the cells based on the results.